Spirits sensory analysis

Branko Drljača

Slap Spirits

Article I wrote for Informator, the journal published by the “Association of Technology Engineers of the Republic of Srpska.”

Spirits sensory analysis

Basics of Sensory Science

Sensory science is an underexplored and highly complex field. It is a science that is not limited, as the general public often believes, to just tastes and smells. Relatively speaking, there is not much literature on sensory science, and what does exist is reduced to a handful of scientific publications that thematically and fundamentally describe its very essence.

Moreover, we must clearly state that sensory knowledge cannot simply be learned from books, even if there were numerous literary series on the subject. How can one explore something so deeply individual, considering that every being perceives and describes what is projected onto them in a unique way? Our personal inclination toward this topic, along with a commitment to researching academic and professional literature, is essential if we are to dive into this endlessly colorful world.

One of the greatest mistakes in sensory science is to start from oneself and assume that you alone are the authoritative benchmark for interpreting all the impressions your environment offers. If we truly want to engage in sensory analysis, we must free ourselves from the notion that one individual can be the ultima ratio (Latin: final authority / decision) in this complex subject matter.

From a practical standpoint, sensory perception can be trained extremely well and effectively. In everyday life, this could include going to the market, preparing food, using spices in the kitchen, visiting restaurants, or taking a walk through nature or the forest after rain—just a few examples where we can develop our senses. If you grew up in the countryside or often visited your grandparents in a rural setting, you already possess a treasure trove of familiar aromas.

Starting from the first spring flowers, eating fresh or cooked fruits and vegetables from the garden, foraged forest produce, humus and moss, fish, domestic animals and their products, dairy items, roasted coffee… etc. A multitude of aromas already reside in our mental files, waiting to be rediscovered and used as vessels for time travel. My personal “time-travel” aromas are what we called “white coffee” and fried bread. These scents instantly teleport me to my grandmother’s sunny rural yard and inevitably awaken emotions.

Aromas don’t only serve as gateways to the past or emotional triggers. Among other things, they are responsible for enhancing quality of life—when we consciously perceive them.

Sensory science deals with the perception, description, and evaluation of a product’s properties based on impressions detected by the sensory organs. In the literature, it is defined as the science of using human senses for the purpose of research and gathering measurable data. (Latin: sentire – to feel / perceive / mentally notice). Sight, smell, taste, hearing, and touch are the five basic senses.

Sensory analysis of products is a scientific discipline based on experimental design and statistical evaluation, which, through a panel of assessors, collects representative results regarding the expression and characteristics of a product. By using statistical methods, these results allow for valid conclusions and insights about the tested product. Relevant aspects include appearance, color, clarity, aroma, taste, typicity, and harmony.

The eye, as our visual receptor—in other words, sight—is the sensory impression detected through the eyes, used in testing and evaluating a product’s sensory attributes. With our eyes, we assess the product’s appearance, color, and clarity.

We use the nose as an olfactory receptor, where during smelling, the chemical signals of molecules are converted into electrical impulses that are sent to the brain via the olfactory bulb (Latin: Bulbus Olfactorius), where they are further evaluated. The nose is used to assess aroma and the typicity of a product.

The mouth functions as a gustatory receptor, transmitting impressions through taste cells, which are primarily located on the tongue but also throughout the oral cavity and throat. There are five basic tastes: sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami (glutamate/aspartate). The discovery of specific receptors in the oral mucosa of humans and other mammals—and their study over the past 15 years—has led to the assumption that metallic and fatty could also be perceived as tastes. However, these two are not yet considered standard aspects of sensory science, as the topic remains insufficiently researched. With the mouth, we evaluate taste and harmony.

Kokumi is a particularly interesting discovery. Like umami, kokumi is a term from Japan, describing the taste sensation we might call balanced, harmonious, or full-bodied. Unlike umami, which defines the flavor of free glutamate and is found in all protein-rich foods, kokumi is not an independent taste like sweet, salty, or umami. Rather, it is more of an effect or sensation that can be noticed when ingredients are combined and acts as a flavor enhancer. Kokumi is primarily formed in fermented foods (aged cheeses, fermented soy) or in long-cooked dishes. This sensation is especially noticeable in meals where legumes (beans, lentils) are combined with protein-rich ingredients such as meat, fish, or tofu, cooked for a sufficient time, and where fat is generously used during preparation. Examples include Cassoulet au Confit d’Oie from southwest France, as well as our traditional Pasulj (beans with bacon).

Spirits sensory analysis

The experience of aromas and flavors accompanies us as something inherent in all aspects of our lives, so natural that we no longer consciously register it.

It simply works.

We must develop awareness of the incredible sensory capabilities behind our perception. Only then do we take the first step toward truly getting to know our senses, living with them more consciously, and engaging with them in a more nuanced way.

To detect aromas and faults in alcoholic beverages, one must first become sensorially sensitized to distillates. This occurs through training and practice, which build the ability to recognize product quality and describe it in words. A very important factor in sensory analysis is the temperature of the distillate during tasting, as well as the shape and size of the glass.

Generally speaking, the temperature of the distillate should be between 16–18°C in a glass shaped like a closed tulip blossom. The level of the distillate in the glass is also essential—it should not exceed the widest part of the glass.

Experts such as sensory analysts, sommeliers, or individuals involved in the production and tasting of strong alcoholic beverages possess a high level of sensory awareness and a professional approach to the field. Most people from the groups mentioned above are likely Supertasters. But what is a Supertaster? Contrary to what the term might suggest, a Supertaster is not someone who can “super-taste” or taste a lot. Rather, a Supertaster is a person with heightened sensitivity to bitterness (taste) due to a genetic predisposition.

Further research into this group has shown that they are not only hypersensitive to bitterness, but also to other tastes and aromas. The olfactory sensitivity threshold in Supertasters is lower compared to someone classified as a Nontaster.

Supertasters tend to be more selective with food, have a lower Body Mass Index (BMI), and consume less alcohol because they experience aromas and flavors more intensely. If we were to say that non-Supertasters perceive aromas in pastel colors, then Supertasters perceive them in neon colors.

It has been proven that People of Color and women are more likely to be Supertasters than white European males. These are important factors to consider when assembling a tasting panel, as it is recommended to diversify its composition. Attention should also be paid to the evaluators’ professional background, education, and occupation.

Globally, approximately 25% of the population are Supertasters, 50% are Normaltasters, and 25% are Nontasters.

The interpretation by a sommelier, as a taster of alcoholic beverages, is often influenced by the technical aspects of the tasting process, which is carried out in a structured and meticulous manner. Its most important components include identifying flaws in the distillate, aroma intensity, persistence, balance, and harmony of the product. The scoring scale typically ranges from 75 to 95 points. Bartenders, on the other hand, are often more subjective, assessing more emotionally and being more radical in point allocation, with scores ranging from 60 to 100 points.

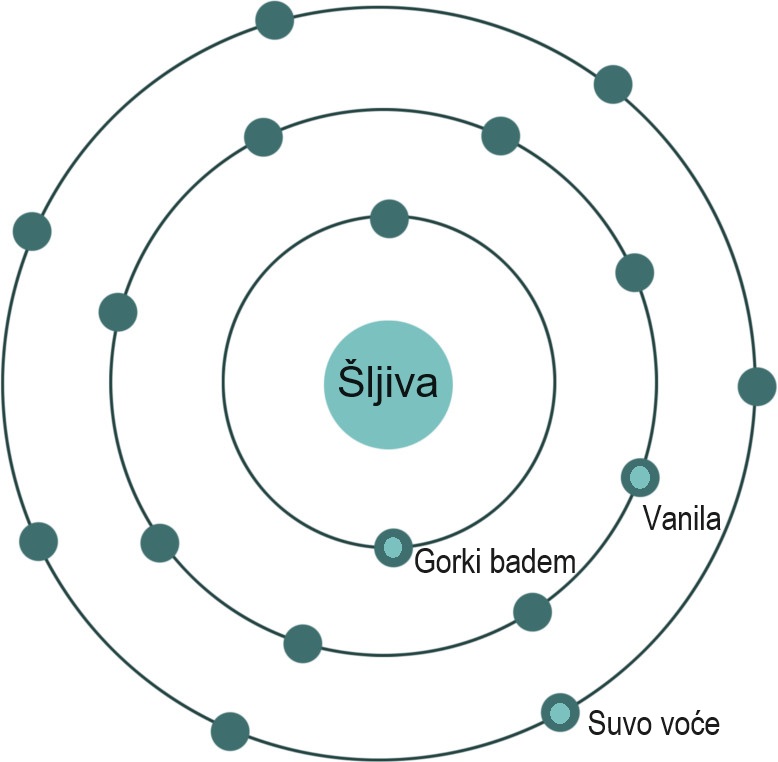

Education and experience are essential factors for objectively evaluating a distillate. Tasting is performed using the cognitive database the taster possesses, and how skillfully they can access stored aromas at a given moment. I would compare the aromatic spectrum of a distillate to Bohr’s model of the atom (Bohr N., 1913). If we say that the primary aroma of a plum brandy is plum, that would represent the core of the aroma. In the first orbital, there might be a bitter almond note; in the second, vanilla; and in the third orbital, dried fruit aromas, and so on.

The color of a strong alcoholic beverage has a significant influence on our subjective perception. Darker shades can easily suggest aromas that, from a chemical standpoint, are not actually present in the distillate. For example, from a very dark barrel-aged spirit, we subconsciously begin to expect aromas such as chocolate, bitter almond, leather, clove, coconut, and the like. Red tones tend to give the impression that a drink is sweeter than it actually is.

But it’s not just the color of the distillate that influences our perception. The color of the room, the walls, a leather armchair, a wool carpet, a rustic wooden table, and even the lighting in the space we’re in can subconsciously affect our impressions. The cushions we sit on and the music we listen to are also factors that inevitably alter our perception.

A test was conducted in which evaluators wore headphones while tasting samples, with different types of music being played. A clear difference in scores was observed when comparing melodic jazz to intense heavy metal compositions. Tasting while seated on uncomfortable metal chairs versus a cozy sofa also yielded noticeably different results. In gastronomy, it has been established that people drink faster when fast music is played, whereas with easy listening music, drinking is slower but of higher quality.

This serves as evidence that sensory perception, through human intellect, consciousness, and the subconscious, interacts with colors, music, life situations, and more.

The subconscious is a trap that only professionals can suppress to a certain extent—but never fully eliminate.

Aromas and Vocabulary

The scent of a product contains all the volatile components present in it. This is an extremely complex structure that can consist of 400 to 800 chemical compounds. We often detect familiar smells that we cannot precisely classify or identify. However, once the identity of these seemingly unrecognizable scents is revealed, they become unmistakably clear (the “Aha effect”).

It is generally believed that humans can recognize around 10,000 different scents. A 2014 study revised that number to one trillion detectable smells. This highly abstract figure stems from the fact that, for example, the scent of a rose consists of 275 individual components. Nevertheless, I would stick with the more realistic estimate of 10,000 aromas.

The essence of aroma is not the five basic tastes—sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami—which are perceived by the taste receptors in the oral cavity, but rather the diversity of substances detected through the sense of smell. Aroma is often defined as a combination of smell and taste. This is incorrect, as aroma is a product of material nature (chemical compounds in the form of molecules), while smell and taste are two of the five main human senses.

Aroma is the sum of all olfactory sensory impressions that arise during orthonasal and retronasal smelling. Sensory analysis is, among other things, the mental memorization of aromas into your personal database.

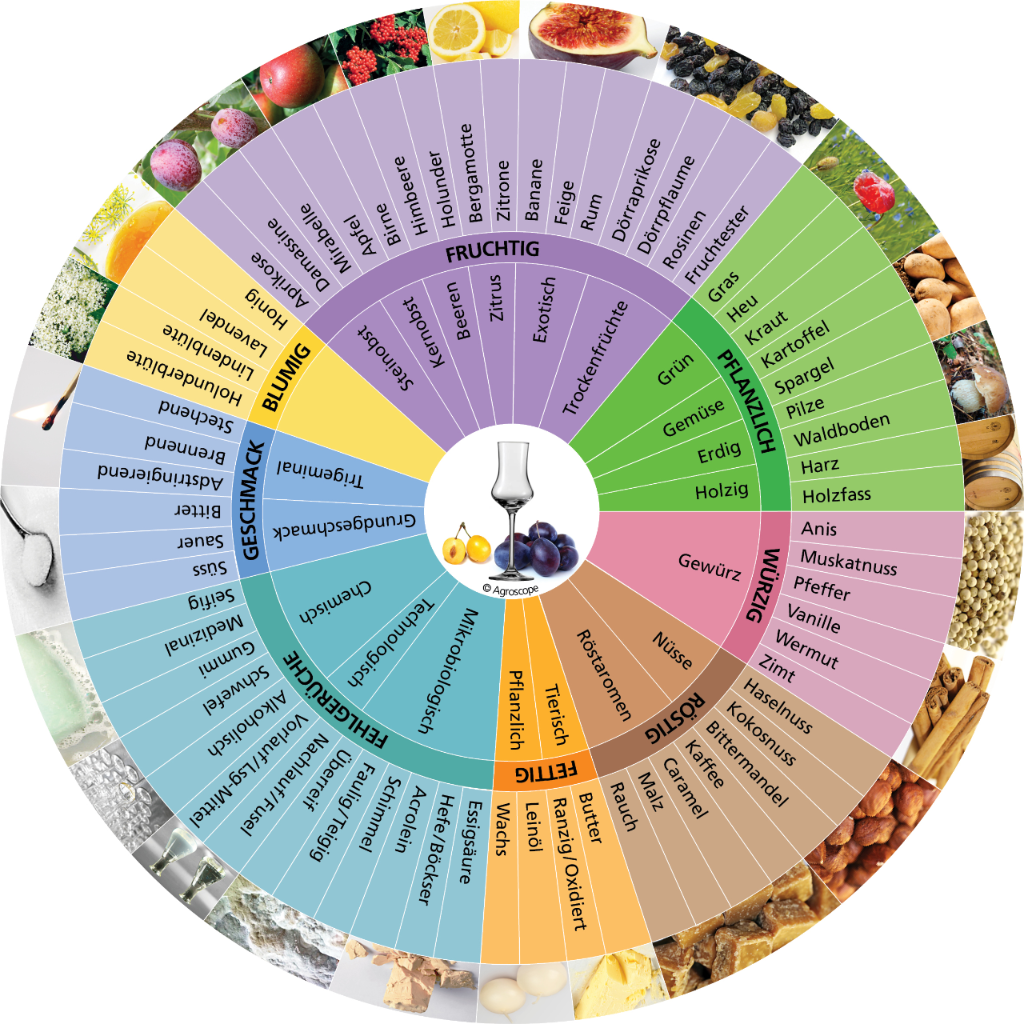

Aromas, along with their positive and negative attributes, are perceived organoleptically and serve as indicators of high quality or faults in the distillate. Structured learning, systematic training, and goal-oriented aroma analysis enable us to properly evaluate a product through human-sensory tasting. Through sensory analysis, we can draw conclusions about the raw materials and production techniques. Practice helps us reliably identify aromas and perform quality classification. Aroma wheels are extremely useful and can serve as helpful tools and reminders.

There are aromas that are typical for a distillate and unpleasant aromas (off-flavors), which vary in intensity. Their presence should be identified even if they are not absolutely clear or pronounced. This is how we recognize a high-quality product and distinguish it from one with faults. This is a highly relevant factor in any form of consumption—be it evaluation, tasting, drinking culture, or the enjoyment factor.

The smell of money (coins) that we perceive when holding coins in our hand is the only aroma without a purely biological origin. It occurs only when metal ions (such as copper) combine with fatty acids from our skin.

The use of specialized vocabulary is certainly something that must be learned and mastered in order to be used confidently in any situation. Describing a product can be quite challenging for several reasons. One of the main reasons is that we always experience taste holistically—as a whole. All aromas and flavor components reach our receptors simultaneously, and as a result of the interaction of all sensorially active substances, they transmit and provide us with the impression or “typical taste” of the drink or food.

Language, however, can only describe this holistic impression linearly—one element after another! This means that during verbal presentation, we list the aromas of a distillate one by one. We do the same with other organoleptic effects such as astringency, trigeminal sensation, bitterness, sweetness, and all other attributes we perceive. An ambitious sensory analyst can convert holistic data into a linear framework through evaluation so that even a casual consumer, amateur, or layperson can understand it. Describing a distillate is a demanding discipline that can and must be practiced.

In addition to practicing sensory evaluation in everyday life, there is the option to undergo structured training. Primarily, this involves formal education for sensory analysts at relevant institutions, where after completing the training, one takes an exam and receives a diploma. This diploma is not valid indefinitely; it must be renewed every five years by providing proof of continued activity in the field of sensory analysis or by retaking the exam. This ensures the quality of sensory analysts for the protection of both consumers and producers.

The second option is self-initiated autodidactic learning, which is naturally a more difficult path. In this case, I recommend a thorough study of theoretical material before beginning practical training.

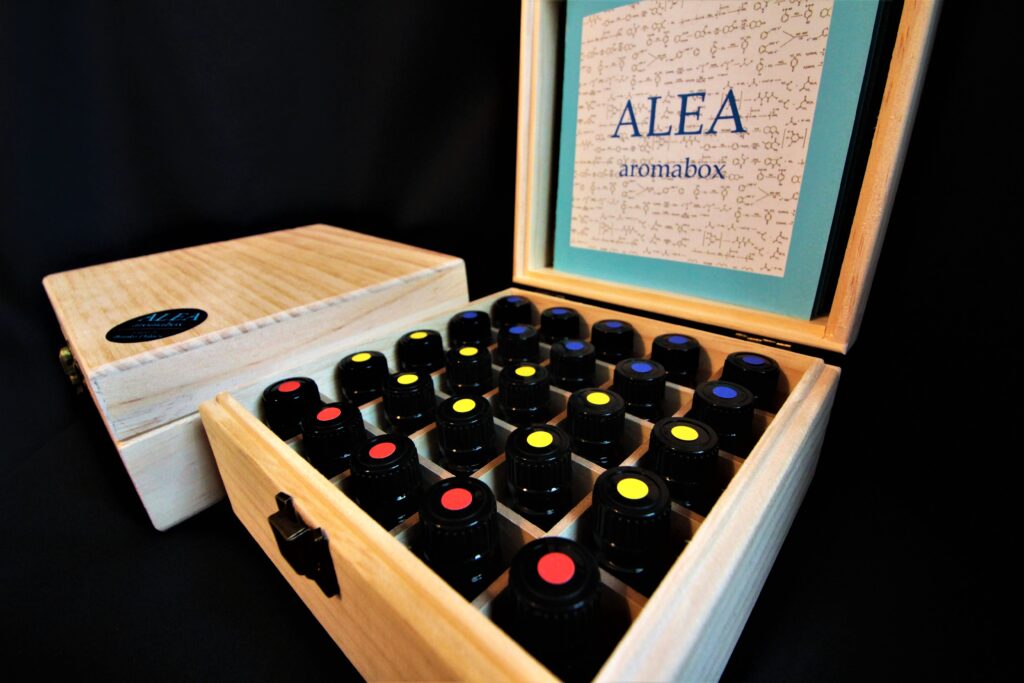

The Aromabox is one of the suitable tools used to begin understanding the basic framework of human-sensory analysis. It is an instrument for sensitizing the olfactory system. The essential aspect is that typical aromas of fruit distillates are isolated and presented as natural aromas in bottles for training purposes. Synthetic aromas, such as those found in wine aroma kits, have not proven to be effective. If you want to learn what vanilla smells like, you should not train with vanilla sugar but with a natural Bourbon vanilla pod. An additional benefit of training with isolated aromas is that it can help you quickly determine whether you have anosmia to certain aromas.

It is important to first learn pure natural aromas without the influence of other attributes, in order to later recognize and isolate them from the aromatic spectrum (Fr. bouquet) of a strong alcoholic beverage. A good example is the aroma of coffee, which we detect very quickly and can relatively easily distinguish from the overall aroma of the distillate because we are so familiar with it. Through training, we are able to enhance our sensitivity to specific aromas. I have proven that with daily, intensive practice using the Aromabox over a period of three weeks, it is possible to drastically improve sensitivity to aromas that were previously not perceived strongly enough.

If you start practicing, you’ll likely encounter situations where you perceive a rose aroma, while the person next to you detects jasmine or lilac in the same distillate you’re tasting. Everyone is right, and the reason is that each person has their own individual impression of the aromas they perceive. That’s why it’s odd that some producers of fruit distillates adjust their products to meet the aromatic preferences of the market or believe their brandy should possess aromas that are currently en vogue. It’s perfectly fine if someone doesn’t like your product—everything is a matter of individual perception. This has long been recognized, and we know that “there’s no disputing taste” (lat. De gustibus non est disputandum).

Download the magazine.